As a budding horticulturist, my first encounter with prairie dock (Silphium terebinthinaceum) was intriguing and puzzling. The sheer size and verticality of the spade-like leaves slicing through grasses and forbs captured my imagination, and while its place in the University of Wisconsin’s Curtis Prairie provided a clue to its nativity, its identity was a mystery. Over the ensuing years I came to know prairie dock well, thanks to its prominent position in certain naturalistic areas at the Chicago Botanic Garden. It honestly delights me in every season. From the unfurling spring-green foliage to the brown autumnal leaves, twisting and curling on themselves, to the starkness of the dark, wizened husks poking through a crystalline snowfall, I love this plant. To this day, the sight of its sunny daisies anchored by the prodigious foliage is both nostalgic and heartening.

So let’s talk about rosinweeds, the catchall common name for many Silphium. The comments I hear most often are rarely effusive but rather succinct: too big, too wild, too weedy, too yellow. The likability of yellow aside, let’s consider those other descriptors, as they are what ultimately led to our trial—well, two trials to be exact. I made a novice’s mistake by not giving these plants enough room in the 2002 trial, so I spread them wider in the second trial nearly 20 years later, or so I thought. My calculations were still off; their battle for space is best described as a clash of the titans. I think many rosinweeds might be too big or too wild-looking for some folks to appreciate, but it is their over-the-top size and strong architecture that makes them so unique in the garden. And our trials proved that several species are well worth finding room for. I’ll leave you to decide if yellow is a problem.

Learn more:

Rosinweeds (Silphium sp. and cvs.)

TRIAL PARAMETERS

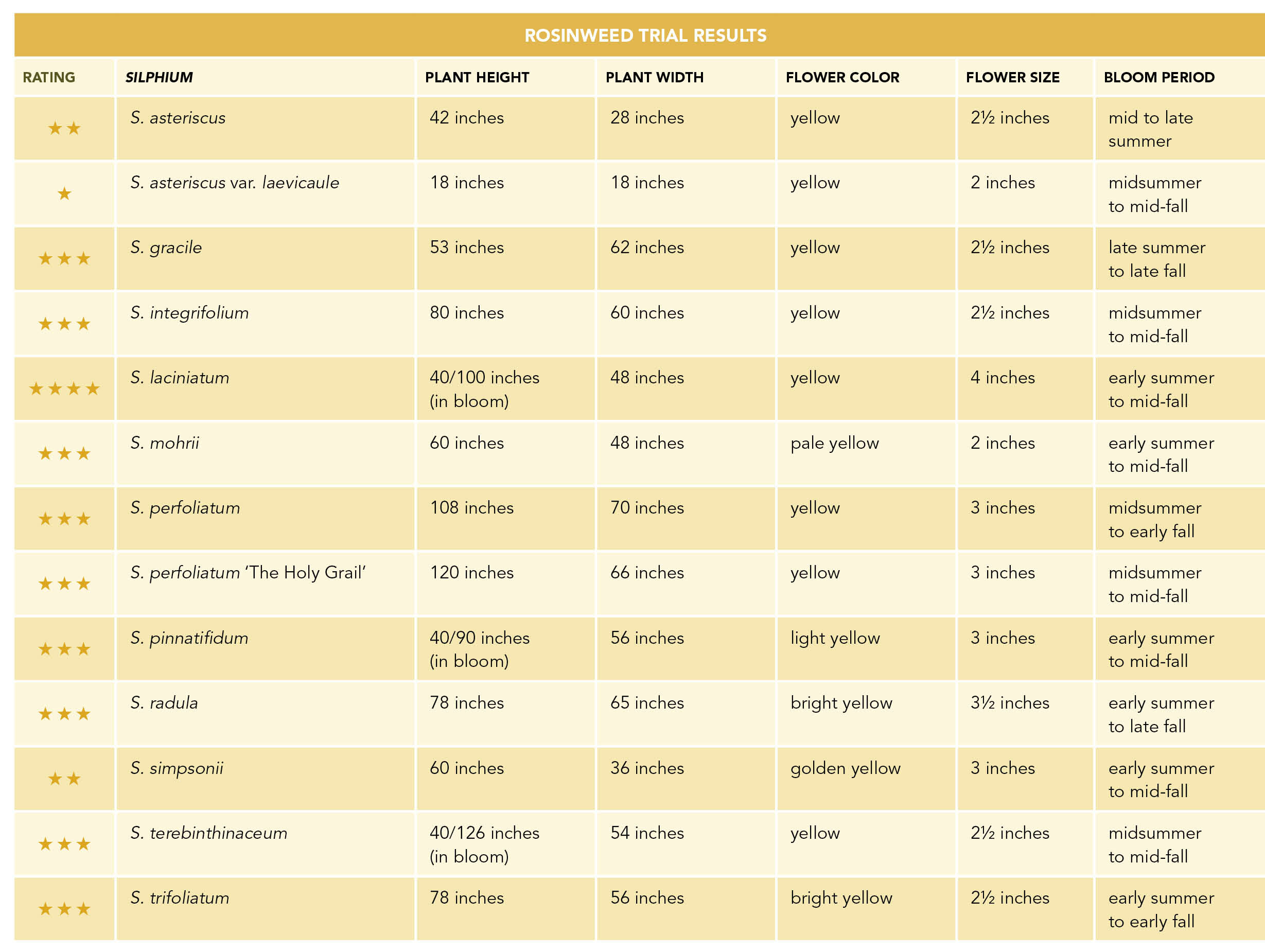

The Chicago Botanic Garden evaluated 13 rosinweeds between 2002 and 2024. All specimens were mail ordered except for S. radula, which was wild-collected in East Texas in 2019, and S.

perfoliatum ‘The Holy Grail’, obtained locally from its originator. The seed-grown nature of the species accounts for habit and plant size variations observed within each taxon.

How Long: Minimum four years

Zone: 6

Conditions: Full sun; well-drained, alkaline, clay loam soil

Care: We provided minimal care, allowing the plants to thrive or fail under natural conditions. Besides observing their ornamental traits, we monitored them to see how well they grew and adapted to environmental and soil conditions while keeping a close eye on any disease or pest problems and assessing plant injury or losses over winter.

Top Performers That Make a Bold Statement and Encourage Biodiversity

When it comes to impressive texture, compass plant (S. laciniatum) is hard to beat. This plant features deeply lobed, sandpaper-rough leaves that are big (24 inches long and 18 inches wide). Like the well-known prairie dock, the basal foliage stands vertically. The common name refers to the orientation of the leaf blades, which face east and west to take advantage of early morning and late afternoon sun while avoiding the desiccating hot midday sun. Flower stems rose to over 8 feet above the tall leafy bases—and all of this with a whole lot of taproot (12 feet) below. These plants did get quite wide over time, but some of the girth was due to stems splaying under the weight of the flowers. The 4-inch yellow blooms—the largest in the trial—are borne along thick, beet red–tinged stems from early summer to mid-fall. The chunky phyllaries are bristly and lack fragrance. Compass plant is native to prairies, glades, and disturbed habitats from Wisconsin and Minnesota, south to Louisiana and Texas. Resist the urge to put this giant at the back of a bed, border, or meadow—the large foliage is better appreciated near the front. And taking a cue from its prairie habitat, pair it with grasses and perennials that accentuate the foliage but won’t mask the flowers, such as little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium, Zones 3–9), smooth blue aster (Symphyotrichum laeve, Zones 3–8), and flowering spurge (Euphorbia corollate, Zones 3–9).

I’m sticking with prairie dock (S. terebinthinaceum) as my favorite of this plant group. Once seen, it’s not forgotten—mastering the botanical spelling and pronunciation was a bit of a challenge, though. Dark yellow flowers cupped in smooth green phyllaries opened nearly a month later than compass plant and had a shorter overall bloom period. The slender, nearly naked flower stems were the tallest in our trial at 126 inches. The broad shovelhead-like basal leaves were 2 feet long, or maybe “tall” is a better word, as they stand vertically. Like compass plant, the thick, sandpapery leaves orient north to south, thus reducing moisture loss through transpiration and keeping leaf surfaces cool to the touch on hot days. A deep taproot helps prairie dock survive extreme droughts. Surprisingly, rabbits and deer occasionally munched the rough leaves but left other plants in the trial alone. To be at its best, I feel like prairie dock would prefer leaner soil and the company of other plants rather than just hanging out by itself. In our prair-ies I love it with flowering spurge because the bright white clouds of baby’s breath–like flowers soften the sharpness of the large prairie dock leaves. And let the branched flower clusters have their space by planting companions closer to the height of the leafy clumps. Magenta-flowered winecup (Callirhoe involucrata, Zones 4–9) clambering over and through prairie dock foliage is a particularly brilliant combination. This species is primarily native to the central United States from Wisconsin south to Mississippi.

Roughstem rosinweed (S. radula) is a standout for a few reasons—it blooms later, into late fall here—and its big rosette-shaped phyllaries are pretty cool. The bright yellow flowers are 3 to 4 inches across with broad, overlapping rays that make them look more substantial than the spidery blossoms of others in this genus. It’s also a heavy bloomer, with hundreds of flowers produced at the top. The coarse-textured phyllaries look like green roses before and after flowering and are quite large at 1½ inches wide. Many of the leafy-stemmed rosinweeds drop their foliage and look a bit shabby by late fall, but roughstem rosinweed’s stiff, scratchy leaves stayed green longer. At 6½ feet tall and almost as wide, this species is too big and bushy for the front of a bed or meadow. But in the back or middle it mixes nicely with coneflowers (Echinacea spp. and cvs., Zones 3–9), ironweeds (Vernonia spp. and cvs., Zones 4–9), and tall to mid-sized grasses. For a southern native—South Carolina west to Texas and south from Missouri to the Gulf of Mexico—it did well in our northern clime.

Whorled rosinweed (S. trifoliatum) is probably the best-looking rosinweed late into autumn because its leaves are still mostly green and stay attached into November! The scabrous dark green leaves are arranged in whorls of three, or sometimes borne oppositely on smooth burgundy-tinged stems. It has a finer texture than most as the leaves are only 4 inches long and just over an inch wide. The bushy, vase-shaped habit is attractive, and the tall stems remained upright most of the time, although relaxed somewhat during heavy peak bloom. The bright yellow flowers are more starlike, since the ray florets do not overlap and are plentiful from early summer to early fall. Big bluestem (Andropogon gerardii, Zones 3–9), beebalm (Monarda didyma, Zones 4–8), and pitcher sage (Salvia azurea, Zones 4–9) are good matches for scale and texture. Whorled rosinweed is native to prairies and roadsides east of the Mississippi River from Pennsylvania and Ohio, south to North Carolina and Alabama.

Starry rosinweed (S. asteriscus) gets an honorary mention despite its less than stellar performance. I wanted so badly for it to make my top-picks list because of its lemony yellow flowers and short stature; there aren’t many Silphium options for smaller gardens. Unfortunately, starry rosinweed wasn’t as cold hardy as other species—only one of the five plants survived through 2024. It is a southern native from Tennessee to Florida, and since our seed came from a Florida mail-order nursery, we assumed it had a southern provenance. I would like to try seed from a potentially hardier locale—native populations purportedly come as far north as southern Illinois. The cheerful starlike flowers bloom from mid to late summer and have 1-inch-wide leafy phyllaries with a strong medicinal fragrance when bruised or crushed. The 5-inch green leaves are less rough than other rosinweeds and are arranged alternately on burgundy-tinged green stems. Try it if you garden in warmer zones, or protect it in colder areas and couple it with mounding asters, little bluestem, and a shorter ironweed like ‘Summer’s Swan Song’.

I admit that cup plant (S. perfoliatum) scares me a little. It’s not the ginormous size—that actually intrigues me, as do the conjoined opposite leaves, which form cups that hold rainwater and dew for birds and bees to drink. My nervousness stems from how quickly and widely it can spread to form colonies. While I hate to think all it takes to sway me is a little color enhancement, ‘The Holy Grail’ cup plant did just that. The enormous jagged leaves are yellow early in the spring before fading to chartreuse and then to bright green from late spring on. Yellow flowers cluster at the top of 10-foot-tall stems from midsummer to mid-fall; the 3-inch flowers are not proportional to the exuberant size!

The phyllaries and stout, square stems are hairless, while the large leaves (15 inches long and 11 inches wide) are rough. ‘The Holy Grail’—introduced by Intrinsic Perennial Gardens—has a tighter and more upright habit than the species, which is native to wet places from Quebec to Georgia, and west to Nebraska and Kansas. It is best in large beds and meadows or near water, planted with other moisture lovers such as Joe Pye weed (Eutrochium maculatum, Zones 4–8), queen of the prairie (Filipendula rubra, Zones 3–9), and ‘Skyracer’ purple moor grass (Molinia caerulea subsp. arundinacea ‘Skyracer’, Zones 5–8).

The smaller stature of Mohr’s rosinweed (S. mohrii) will appeal to gardeners who might be nervous about its bigger cousins. At 5 feet tall and 4 feet wide, it was one of the shortest rosinweeds in the trial. For nearly three months, beginning in early summer, abundant 2-inch pale yellow flowers put on a nice show (photo p. 48). Their light almond or vanilla scent is an unexpected treat that people and pollinators adore. Mohr’s rosinweed is noticeably fuzzy all over—more so than any other species—making the green leaves, stems, and phyllaries look grayish (photo p. 56, bottom). Unfortunately, it has a messy downside—the withered ray florets fall and cling to the fuzzy leaves as does other organic debris. Mohr’s rosinweed is a prairie native in Tennessee, Alabama, and Georgia, but has been fully hardy in the upper Midwest. The bushy habit can be softened by billowy asters, catmints (Nepeta racemosa and cvs., Zones 4–8), and grasses, both short and tall.

| CULTURE TIPS |

Traditionally, this group of plants is low-maintenance when sited correctly in the landscape. The biggest challenge lies in—well, their bigness. The shortest rosinweed in our trial was still 5 feet tall and nearly as wide, so if you want to grow these native perennials (and you should), you’ll need to have adequate space. Here are some other things to note when it comes to these giant plants.

The blooms may be small, but they’re profuse. The flowers—shades from pale to golden yellow—have a central disk surrounded by petal-like ray florets and look much like their sunflower (Helianthus spp. and cvs.) cousins. The ray florets of rosinweeds are fertile and produce seeds, while the disk florets are just for show. Flowers range from 2 to 4 inches wide and seem undersized on such large plants, but their great abundance makes up for it.

You’ll notice the phyllaries. The flowers have prominent stiff phyllaries—reduced leaf-like structures that form one or more whorls immediately below the flower head. Think of a phyllary as a leafy cup that flowers sit within. The character of phyllaries varies by species and aids in identification.

Pollinators are plentiful and diverse. Honeybees, native bees, leafcutter bees, monarchs, tiger swallowtails, skippers, and fritillaries all feed on rosinweed nectar, while birds such as American goldfinches and black-capped chickadees forage for the seeds. Most Silphium species are also host plants for an assortment of butterflies and moths, including the aptly named silphium moth (Papaipema silphii).

Watch out for reseeding. Although most of the species are quite robust, there is one Silphium that is bigger (and more thuggish) than the rest. Deadheading might be a good idea for cup plant (S. perfoliatum, pictured) as it can be a vigorous seeder and could quickly overtake a sizable corner of the landscape if not kept in check.

| Sources |

Prairie Nursery, Westfield, WI; 800-476-9453; prairienursery.com

Camp Creek Native Plants, New Albany, MS; 662-539-7175; campcreeknativeplants.com

Prairie Moon Nursery, Winona, MN; 507-452-1362; prairiemoon.com

Native Plants Unlimited, Fishers, IN; 317-777-9469; nativeplantsunlimitedshop.com

Contributing editor Richard Hawke is the director of ornamental plant research at the Chicago Botanic Garden in Glencoe, Illinois.

Fine Gardening Recommended Products

A.M. Leonard Deluxe Soil Knife & Leather Sheath Combo

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

MULTITASKING DUAL EDGES: a deep serrated edge and a tapered slicing edge ideal for tough or delicate cuts. DURABLE 6-inch stainless steel blade withstands 300 lbs of pressure. TWINE CUTTING NOTCH, DEPTH GAUGE MARKINGS & spear point – no need to switch tools when using this garden knife. LEATHER SHEATH: heavy duty, protective, clip on sheath to keep your knife convenient and secure. LIFETIME WARRANTY.